“I have only what I remember,” by Rebecca Morse, Curator, Wallis Annenberg Photography Department at LACMA

“The centerplace of the house, like the body, accumulates memories that may have the characteristics of ‘feelings’ rather than data. Rituals over time leave their impression on the walls and forms of the interior endow the rooms with artifacts which give us access to previous experiences.”1

A young girl sits at a baby grand piano, looking intently at the keys while she plays. Her neatly combed hair and red velvet dress suggest a holiday performance for the family. Above her head a painted bulbous figure emerges from a modeled crimson foreground, writhing in discomfort. The girl is nonplussed by the expressionistic Francis Bacon painting or the swirl of artwork around her – from colorful cutouts to the piercing eye of an unearthly figure − and appears to march along through the musical piece at her fingertips. Time is fluid in this photograph, as the dates in the title suggest: Bacon (1985, 1992, 1992, 2008), each year collapsed upon another and, like our own lives, a series of stills that are not fixed, but in a continuous, cyclical motion.

Each of us is connected to our past through memories we have filed away, created through our own lived experiences or the photographic documents made by others. Cognitive psychologists characterize those memories in visual terms by describing them as “a vast network of connected images and thoughts, something like a series of nets or webs.”2 This netting is like a flexible framework, upon which ideas, images, and emotions become tangled and adhere, as time passes. They cluster, they overlap, some are sharp and some are faded, some are colorful, others are gray, and some ultimately slip away. Accuracy is subjective and as the particulars group together in our minds, they contain not only the physical details of the past, but also the raw emotions that are embedded within.3

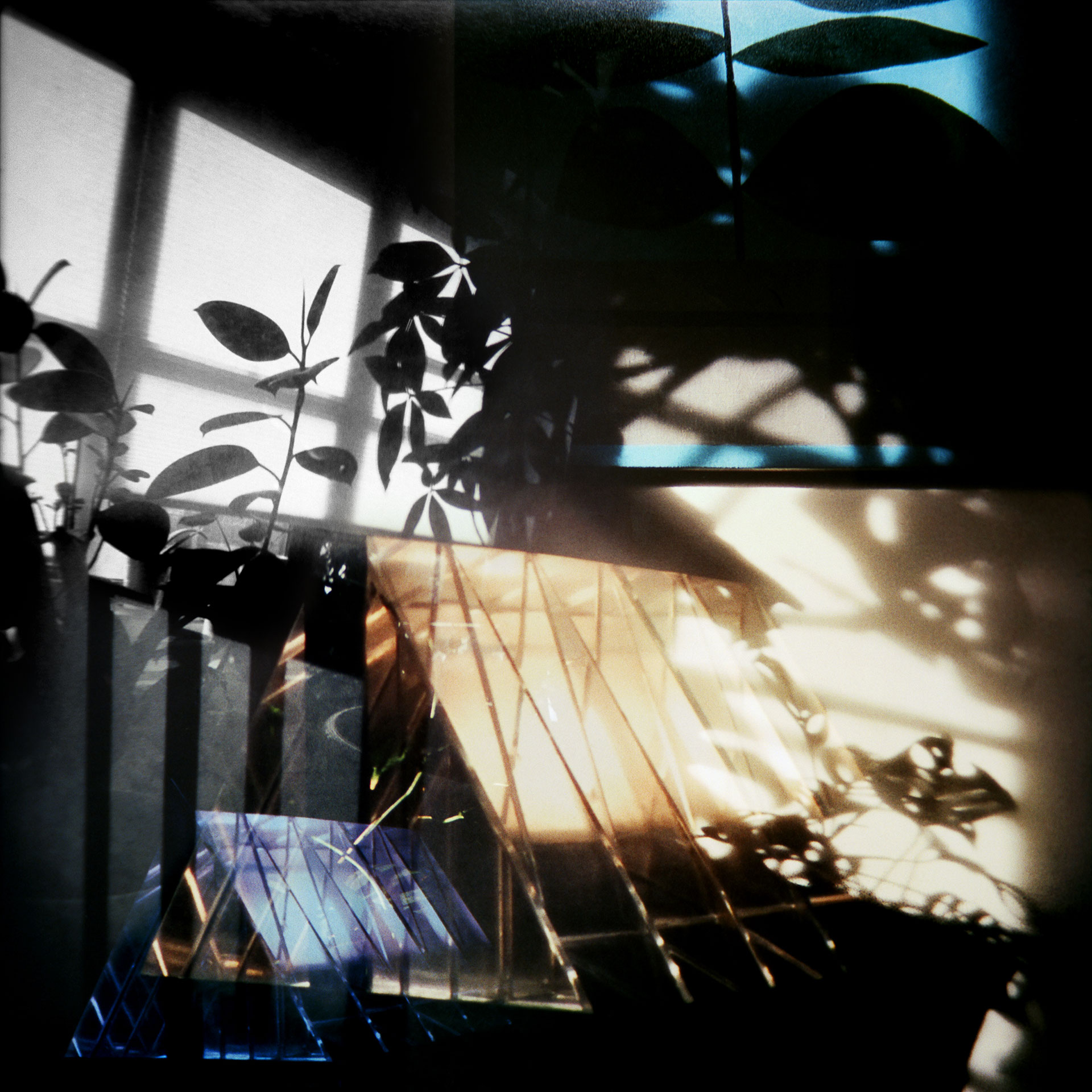

I have only what I remember lyrically expresses the way our brains synthesize the past. Each photograph within the series contains multiple scenes, layered over one another, and captured as a single image. The setting is the modernist home of Augusta Wood’s grandparents photographed at different points in the life of the family. The earliest date is 1951, just prior to the commissioning of the house by Wood’s grandparents, and the most recent is 2008, when Wood gained access to the empty house after the death of her grandfather and just prior to its sale. It was at this time Wood began exploring the influence of the residence as a formative environment for her as an artist.

In Gaston Bachelard’s “Poetics of Space” he establishes the home as “an imaginary or mnemonic realm in which architectural structures are synecdoches for the emotional states defining self-hood.”4 As we embark on the process of creating our own identities in childhood, we establish significant bonds with the places where emotional events occurred, particularly within the home.5 I have only what I remember presents a labyrinth of paneled media rooms, mossy carports, work spaces, and theatrical bathrooms in which rich visual narratives are presented. Made with overlapping slides from the family archive projected onto the walls of the house, Wood touches upon the moments that were instrumental in the creation of her personal and artistic identity.

Significant examples of twentieth century artwork punctuate nearly every image. In the photograph HF, JM, RL, Posy (1983, 1985, 1996, 2002, 2008), the attitude toward the family’s art collection is revealed—Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Miró, and Roy Lichtenstein in an overlapping jumble, are adjacent to an image of Wood’s grandmother “Posy” dressed in a winter coat and holding a hand bag, either heading out or returning home. In this house, these paintings are quotidian objects that exist easily alongside the everyday actions of the family; here art and artists are a part of life. Rosy’s Studio with Blue Jackie (1990, 1991, 2004, 2008) channels the viewer into Wood’s grandfather’s workplace where, among his own artwork, is hung Andy Warhol’s 1964 silkscreen of Jacqueline Kennedy. Hierarchy is abandoned and the mourning First Lady, as Pop icon, shares the same space as Grandpa’s exploratory abstractions. This juxtaposition echoes the trajectory of twentieth century art history from Abstract Expressionism to Pop.

Each photograph is a story, an encapsulated mix of architecture, objects, and family. While Wood has engaged with storytelling in previous bodies of work, often inserting written lines of text within the scene before rendering them photographically, here she uses juxtaposition of objects, individuals, and site as a narrative device. The employment of this storytelling strategy is tied to mid-century literature, originating in the late 1950s with the Nouveau Roman where writers, such as Alain Robbe-Grillet, sought freedom from the traditional novel’s occupation with straight plot. By revealing the story over time, rather than telling it explicitly to the reader, the author adhered more closely to the non-linear flow of human experience, which rarely has decisive starts and finishes. Robbe-Grillet’s approach focused primarily on objects in the world rather than character and plot, moving fluidly from a description of a man’s elastic trimmed trousers to a movie poster describing a Herculean figure in Renaissance costume.6 Perfectly fit for a visual application, this approach was applied to filmmaking as seen in Last Year in Marienbad (1961) by Alain Robbe-Grillet and director Alain Resnais. Past and present are intercut and punctuated with repeated conversations and long shots of hotel corridors where guests are gathered for the weekend. The story assembles itself with individuals and objects, but meaning is ultimately formed by the viewer. Wood builds upon these tenets, forming a rich network of subject and object through a veritable time-lapsed trajectory made possible by the use of image overlay through slide projection.

Beginning in the 1960s, as artists were increasingly abandoning traditional methods of art making, slides and slide projections became a fertile medium for exploration. In Los Angeles, artists such as Robert Heinecken were experimenting with projecting slides of text and image on moving nude figures in order to capture those fleeting chance intersections with a 35mm camera. Works such as Then People Forget You (1965) and Man and Figure (1965) reveal unexpected combinations of words, pictures, and the human body.7 In New York, performance and dance-based artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Marina Abramovic, and Yvonne Rainer projected slides from mass media and pop culture onto the performers and performance spaces. For these artists, the insertion of the mainstream into the artistic arena became a political act.8 Other artists, who employed slide installations and singular projections found this approach to be the optimum way to create a collective viewing experience and compete with the size of painting and sculpture through photographic means. Earth artists and Conceptual artists in particular instituted the slide projection as the perfect disseminator of their ideas and projects that were physically or intellectually located outside the traditional gallery structure. As large as paintings, as crisp as photographs, and as engaging as film, slides were embraced by artists such as Robert Smithson, Dan Graham, and Ana Mendieta who liberated this humble medium from the walls of the living room to the walls of the museum.

However, with the rise of PowerPoint in the early 1990s9, and the digital world having absorbed the physical/analogue realm where slides held sway, Kodak responded in the fall of 2004 by discontinuing its only slide projector on the market, the Ektagraphic. For many, personal archives still overflowed with perfectly intact slides and the desire to show and experience them had decidedly not waned. In 2008 Wood inherited the entirety of her family’s slide collection, and together with the opportunity to access the family home for one last time, she embarked on combining the present with the past. Here her own vision, combined with that of those who took the original slides and the architecture of the house itself, makes up the beautifully complex, open ended-photographs of I have only what I remember.

In Safari Room (1993, 2002, 2008), the circular inlaid table is the platform for the assembly of photographs brought together by multiple exposures. Wallet sized and black-and-white formal portraits, images of couples kissing and children in the snow – these combined scenes capture the lives of the house’s inhabitants. But just below that vivacity, is an empty corner forcing the realization that the crowded past shares the space with the hollow present. The story emerges as the eye darts among the objects. Perhaps it is one of these children who is pictured elsewhere in the series, perched inches away from the color television, watching Ernie and Cookie Monster act out their endearing routine on Sesame Street. Below her a pair of toddler legs emerges and the palette of the TV program, collection of LPs, and a child’s knit sweater together date the projected scene as the early 1980s. Just to the right, is the red light of contemporary electronics—a charger or alarm, and the present collides physically with the past.

Drawing at 1, Moving Boxes at Night (1951, 1951, 2003, 2005, 2008) parenthetically frames the project, conceptually and chronologically. Drawing at 1 refers to a notation in Wood’s grandmother’s datebook reserving time in the day to make drawings. The prioritization of artmaking by a 1950s homemaker speaks to art’s centrality in the life of this family, which permeated her granddaughter’s upbringing on through adulthood. Seen from the exterior, that handwritten note occupies two rooms of the house, where the activity of drawing ensued, and the remaining rooms are lit in a kaleidoscope of color, image, and shadow. The central picture shows the contents of the house packed into brown cardboard boxes pending relocation. A span of fifty-seven years is represented by this photographic mind-map of Wood’s relationship to the house, artwork, and individuals contained within. Each node, layered with objects and their associated memories, tells this artist’s story.

1 Kent C. Bloomer and Charles W. Moore. Body, Memory, and Architecture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1977), pp. 49-50.

2 Jerry M. Berger, Returning Home: Reconnecting with Our Childhoods (Lanham, Maryland: Roman & Littlefield Publishishers, Inc., 2011), p. 23.

3 Ibid, p. 24.

4 James Krasner, Home Bodies: Tactile Experience in Domestic Space (Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2010), p. 6.

5 Ibid, p. 31.

6 Alain Robbe-Grillet, translated by Richard Howard, The Voyeur (New York: Grace Weidenfeld, 1986), p. 65.

7 Heineken was also influenced by Alain Robbe-Grillet and first saw Last Year in Marienbad in 1971/1972 before exploring his movies. This information was learned during a conversation with the artist in spring 1996.

8 Darcie Alexander, Slideshow, exh. cat (Baltimore: The Baltimore Museum of Art, 1995), p. 21.

9 Ibid, p. 31

© 2014 Rebecca Morse